|

|

|

Deal Directly with the sellers, and save time and money. Please mention EN RADA when you call / e-mail. |

|

All negotiations and sales are between seller and buyer. |

|

For Sale |

|

Cannon |

Bibliography |

Available |

|

HI! I’m Roy Volker, long-time treasure salvager on the 1715 fleet on Florida’s “Treasure Coast” and author of Treasure Under Your Feet. The time has come to hang up my mask and fins and let you younger pups take over. I have a great deal here for one of you seasoned TH-ers…or someone just putting a dive operation together. I believe in redundant systems. That is why I have two identical Proton Magnetometers on my operations. If I have the boat out working, especially at a remote site in the Bahamas, Grand Cayman, or elsewhere in the Caribbean, every day’s search or recovery is important to my success. Having two identical Mags aboard has saved my time (and time equals money at sea) many times in the past. Magnetometers are subject to the changes in Earth’s magnetic fields —and to atmospheric conditions as well. If we had a day where one Mag was “acting weird,” we’d plug in the second one for comparison. If both act up, then we are experiencing “atmospherics” and we switch to another phase of our project for the day. If one unit were to break down, we never had to return to port for repair, we just launched the second system and continued our search and survey.OFFER

VOID!

|

|

|

ELSEC

• Direct reading, in Gamma • Up-to date Reliable Integrated Circuits • Digital Indication on Number Tubes • Elaborated Tuning Procedures

Eliminated • Automatic Battery Charging Capability |

Specifications: Field Strength Coverage: 24,000 to 72,000 Gamma in switched rangesSensitivity: +/- 0.5 Gamma Absolute Calibration:

1

part in 100,000 over full temperature range Repetition Rate: 1, 2, 4, 8, 60 Seconds (also by manual pushbuttons) Measurement: Direct Reading in Gammas Display: On 5 digital Nixie tubes; figures 1.5 cm high. |

1733

FLEET

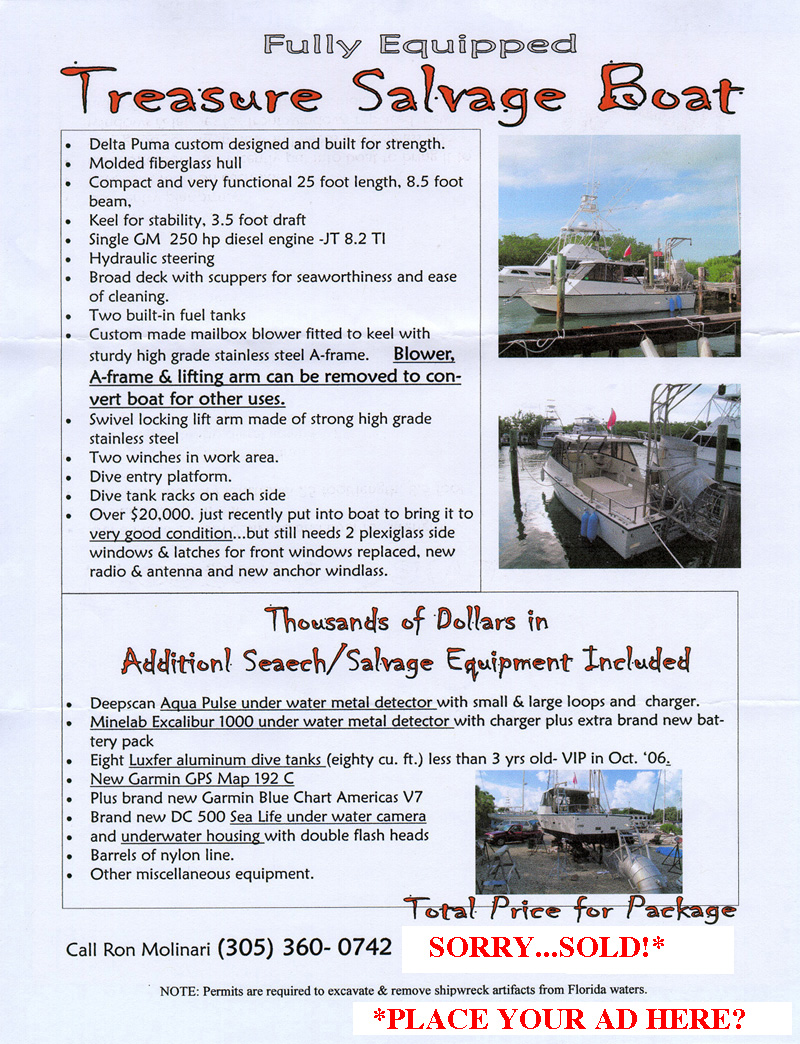

SALVAGE BOAT FOR SALE |

| RETURN TO TOP |

|

|

|

PH: 703-757-7313 ... E-Mail: RealTreasuresBay@aol.com Posted 25 August 2004. |

|

A Colonial Expedient Throughout the

history of the Spanish

exploitation of the New World there was the great temptation of

“salting

away a little something” for oneself. “Saving for a rainy day” as it

were.

As shipwrecks of the period are uncovered and studied, some very

ingenious

methods of hiding contraband on board these returning vessels come to

light.

Thick, one-ounce, 1-1/2-inch long wood screws of silver were found in

the

wreckage of the 1733 Spanish treasure fleet in the Florida Keys; a

six-inch

nail of high-karat gold was recovered from the treasure fleet of 1715

off

Florida’s east coast. And we have seen 7- to 8-inch spikes made of

solid

silver and having “arrowhead-shaped” points reportedly having come from

these wrecks. All would have been screwed or pounded into some plank or

beam on the ship, where they could be retrieved by the owner upon

arrival

in Spain. And all would have been painted over with tar or black paint

to hide their true identities. Smuggling, hiding contraband materials

to

avoid paying taxes (even at the risk of prison or death), was a fact of

life in all colonies of all nations, and the way of all ships and men

at

sea. >>> |

|

|

Ingots —silver

bars and gold bars—

were more difficult to hide from the prying eyes of customs officials

(many

of whom would look the other way for a small consideration!) A ten-inch

bar of nearly pure gold weighing three or four pounds could easily be

stashed

on one’s person or in one’s baggage —but, if found by inspectors…

Perhaps

a couple dozen slice-of-pie shaped silver ingots were retrieved from a

ship of the 1715 plate fleet. Being “wedge” shaped, they gave the name

to the “Wedge Wreck” just north of Ft. Pierce Inlet. When

assembled

as a pie (6 or 8 wedges point to point), they could have been concealed

in the bottom of a keg of, perhaps, tar or rum and hidden from view on

the trip to Spain. Ponderous bricks of silver bullion, as shipped

aboard

the Atocha (sunk in 1622), the “Capitana” (sunk

in

1654), and Las Maravillas (sunk in 1656) were larger

than

breadloaves and weighed 70-90 pounds each, a little too bulky to be

carried

in milady’s handbag. <<< |

| The logistics of shipping and landing this private wealth was eased by paying the king’s tax, the shipper’s fees, and all the various other taxes levied on each ingot … all the way back to Spain, but who wanted to diminish his own wealth by paying all these fees (the king alone got 20% of the value)!!?? Again, from the wreckage of galleons comes the (not-so) surprising answer that not all of these large ingots had been taxed by the king’s appointed officials in the Americas. Many were found without his tax stamp, many bore only marks of the shipper and the intended receiver, and some were not marked at all. …The plot thickens… It is obvious from examining the over 1,000 silver ingots recovered from Nuestra Señora de Atocha that many, many bars, smaller and more manageable in size and weight —all without the prescribed markings— were also cargo on the homebound galleons. vvv |

|

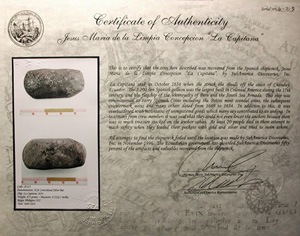

| The 1-1/2-pound

contraband silver

ingot shown here went to the bottom of the Bay of Guayaquíl,

Ecuador

in 1654. Perhaps in the pocket of a passenger, it was traveling aboard

the capitana of the South Seas Armada of that year, Jesús

María de la Límpia Concepción, when the

overladen

galleon sank. At 4-1/4 inches in length, 2-1/10 inches in width, and

3/4

of an inch thick, the ingot is hardly larger than a bar of bath soap,

but

its value was equivalent to about 24 silver pieces-of-eight (at $200

each,

colonial purchasing power) or 1.5 gold 8-escudo doubloons!

--Ernie Richards, EN RADA Publications >>> |

This intriguing example of 17th-century contraband is one of three returned to SubAmerica Discoveries, Inc., in its division with the government of Ecuador. It has not one identifying mark stamped into it, attesting to its illegitimacy, and it displays the rounded edges and discoloration which come from being immersed in salt water and sand for over 300 years. FOR SALE: SORRY! SOLD! This artifact from the capitana

of 1654 comes with a

SubAmerica

Discoveries Certificate of Authentication signed by Sr. Herman

Moro,

resident leaseholder for the site of the ship’s wreckage when it was

discovered.

~~ |

|

|

|

|

|

Re-Posted 02 August 2004 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"The cannonballs are for show only. They are 1-3/4" in diameter and will not fit in the barrel. I made them for the display." |

|

MOTIVATED! NOW $3,500 PLUS SHIPPING! CONTACT OWNER DIRECTLY: "The Cannoneer" 36440 Hillcrest Drive Eastlake, OH 44095 PH: 800/557-1715 (order line) or e-mail:REGLA1715@cs.com |

|

|

|

|

|

“FIND OUT WHAT YOUR COLLECTION IS MISSING!” says the book’s flyer. It lists 750+ titles about sunken treasures, underwater archaeology, shipwreck coins, ceramics & artifacts...with annotations and edition information. The 5-1/2” x 8-1/2” format paperback book is some 400 pages long. Listing at $24.95 plus $3.95 Priority Mail postage in the U.S. (overseas postage at cost.) “Dave’s Treasure Bib” is only available from the author:Dave Crooks, P. O. Box 166, Clarendon Hills, IL 60514. You may ‘phone him at 630/271-9881 or e-mail him at dcrooks@interserv.com. Re-posted 02 August 2004. |

|

|

******************************

|

|

|

|

|

|

|